Robin Mills met Guy Deacon in Chetnole, Dorset

‘My father was in the Army; I liked what he did so I thought I’d do the same sort of thing. I never really thought about it. Being a fireman, doctor, policeman, whatever else, didn’t occur to me. Luckily I passed all the right exams to get in, and ended up doing what I wanted to do, which was fantastic. I thought I’d enjoy it, and I did.

I went to Sherborne School, where I was passionate about sport, particularly rugby, playing lock forward for the First XV. To my parents’ surprise, I also managed to pass 3 A Levels at A, B and C. Soon after the end of my last term, I was on my way to Catterick Camp in North Yorkshire, the start of a life full of adventures.

Joining a regiment is a process which requires more than just a desire on the part of the applicant—you have to convince the regiment that they should invite you. You also need to pass the rigorous selection process, and at Catterick I prepared for this. Most of the people in my intake were weeded out, but thankfully not me. But before officer training at The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, my father had persuaded me I should get a degree; I was fortunate to get a place at Durham University reading Archaeology and Anthropology.

At Durham I met Andrew Hartley, who turned out to be a lifelong friend, and between us we hatched a plan to fulfil a dream of exploring Africa, specifically the Turkana region of Kenya. Teaming up with two other students, and raising the necessary sponsorship, the trip was a great adventure and our reports well received. After that, I was invited to join another trip, a motorised expedition across the Grand Erg Occidental, a remote and challenging part of the Saharan Desert. The beauty of the vast emptiness, the dunes, and the oases shimmering in the heat I will never forget; the seeds for African adventure in later life were sown.

My regiment was the Queen’s Dragoon Guards, one of a number that made up the Royal Armoured Corps. I never wanted to leave the Army, and in the end I stayed nearly 40 years. In my career there were many ups and a few downs, but overall, it was brilliant. I served in Germany, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Belize, Mauritius, and finally the Congo, where I joined a UN peacekeeping mission following the 1994 genocide in neighbouring Rwanda, disarming and demobilising rebel forces. After 18 months in the DRC I returned home, and was honoured to be awarded an OBE for my work there.

That award coincided with less than welcome news. I had noticed a few symptoms that led me to think things weren’t quite right. For example, I couldn’t turn the pages of a book with my right hand, I would stumble and trip occasionally because my right foot was dragging a bit, and bizarrely, I would cry frequently. If I was reading a book or watching a film, I’d get much more emotional about things, which for me was very strange. I was advised to see a neurologist by my nephew, at the time a military doctor in training, who diagnosed me with Parkinson’s disease. My symptoms were all classic Parkinson’s. His words were on the lines of “Bad news is there’s no cure: good news is it won’t kill you. Just take the tablets and you’ll be fine”. I was 49—I felt no anger on learning my fate, but deep depression was something I would have to continually live with. I was given 2 medications on day one, and have been taking the same ones ever since, although by now I’m taking higher dosages and much more frequently. They seem to work quite well, albeit for a shorter period of time, but over the years my symptoms have inevitably become a lot worse.

Despite my diagnosis, the Army, a brilliant employer, allowed me to continue my service, which was of huge benefit to me, and after the Congo mission I held down a number of valuable jobs and was ultimately appointed Colonel RAC, effectively head of the Royal Armoured Corps. I remained committed to the end and the job became my legacy, doing what I could to ensure that the British Army had a credible armoured capability for a somewhat uncertain future, and in that mission I succeeded, and I was awarded a CBE.

The idea of a mostly solo overland trip to Africa first occurred to me in 1980. I was given a book with the cover showing the sun setting behind Landrovers in the desert and thought that’s what I want to do when I grow up, but not until I retired did I have the time and the resources to realise that dream. For someone living with Parkinson’s, this was going to be more than an adventure, it was an odyssey. I thought if I can cope ok in the UK, why not in Africa too, provided I have plenty of pills and can rest when I need to. It turned out I was a bit naïve.

I decided to head for Sierra Leone initially, then would decide on a route after that depending on how things looked. The trip would raise awareness about Parkinson’s, to show that just because you have the condition, with determination you can still do what you want to do; in other words, don’t be defeated. And a major part of that was to set up a blog using the Polar Steps app to record what I had done each day, so people would know what it was like and how I was feeling. In November 2019, I crossed the channel to France.

I chose a 4-wheel drive version of the VW California, which enabled me to camp anywhere without having to set up an external arrangement, providing simplicity and security in remote places. The African roads caused several breakdowns—wheels, tyres, clutch, differential and suspension failures—which caused many holdups, but in all these and other challenges I was met with remarkable helpfulness and ingenuity from local people. Wherever I went, people humbled me with their hospitality and support for my journey.

I had got as far as Sierra Leone, when in 2020 the world stopped spinning—Covid struck. I was advised to return to UK asap, and although my instinct was to wait for a few months for it to blow over, I flew back on an EU emergency evacuation flight. I had no idea it would be 2 years before I could go back, and I had left the van with somebody I’d met 2 weeks before.

Two things happened during lockdown. Firstly, I met Rob Hayward, who suggested we make a film, and I said yes. And I reengaged with Helen Matthews, CEO of Cure Parkinson’s, who told me of key people I should meet when I went back to Africa, in particular Omotolo Thomas, herself diagnosed with Parkinsons at the very early age of 35, who runs Parkinson’s Africa championing the case for the estimated 2.2 million sufferers in Africa for whom medication is either unaffordable or unavailable.

To fund Rob Hayward’s film we shot a promotional video and started a crowdfund, which was a great success. Finally in February 2022 restrictions were lifted, and I returned to Sierra Leone, restarted the wagon with very little trouble, and continued my journey with renewed focus. Along the way there were more breakdowns, often needing spare parts shipped out to Africa in the hand luggage embassy staff or former Army mates. There were interviews with Parkinson’s sufferers I was introduced to on my journey, who were working to reassure the many people who had not been properly diagnosed and believed themselves to be cursed, and interviews on TV stations to raise awareness of the purpose of my trip.

Rob Hayward joined me four times along the way to shoot more film, and was with me when I finally reached Cape Town, the end of my odyssey of 18,000 miles. None of which could have happened without the support of my wife of 29 years, Tania.

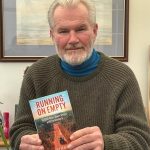

Since my return to the UK, I’ve been incredibly busy, completing my book about the trip Running on Empty, and working on the film with Rob, which is, we believe, to be broadcast on Channel 4 in the autumn. I’m also raising money through my Foundation, (www.guydeacon.co.uk) which is designed to plug the gap in people’s understanding of the disease—that sufferers can be loved and cared for. And—you have guessed it—I plan to return to Cape Town and travel back up the East side of that magnificent continent in 2026.’

Update: Guy Deacon suffered a severe stroke at the end of July 2024. He is making steady progress, but at the time of writing is still in hospital. Unfortunately his book tour for ‘Running on Empty’ has had to be postponed. This has left a large stock of books which his family are keen to sell, as £5 of the cost price of each book goes direct to The Deacon Foundation, a charity Guy set up to help distribute funds to the lowest level in the fight against Parkinson’s Disease in Africa and particularly to address the stigma associated with it.

Running on Empty is a great read and you will be helping an extremely worthy cause. To purchase a copy please visit: https://www.guydeacon.co.uk/the-book