Dr Sam Rose recently revisited Chile to learn more about Tomkins Conservation, an organisation that works closely with government departments, NGOs, local farmers and landowners to support the reintroduction, rehabilitation and acclimatisation of endangered, ‘missing’, and injured wild animals. He describes it as ‘an eye-opener’.

In the 1990s, when former North Face and Esprit clothing owner Doug Tomkins started buying up vast tracts of land in Chilean Patagonia that were at risk of logging, it caused a significant earthquake in a country that is very used to earthquakes. This one was, however, a metaphorical one, and produced much gnashing of teeth from Chileans at the thought of a North American owning so much of their land. Conspiracy theories abounded, but Doug and his wife Kris, insisted that it was for conservation, for biodiversity, for ecosystems, for landscape, and most of all, for Chile.

Nearly 30 years later, the fruits of their inspired and forward-thinking actions are evident throughout Southern Chile, in a ‘Ruta de los Parques’ (route of the parks) with 17 National Parks extending over 2,800km of incredible terrain, five of which were made either wholly or in part from land given back to the state by Doug and Kris. That’s all very well and good, but what has this got to do with the R-word I hear you say? Well, they created a foundation called (you guessed) Tomkins Conservation, and, in time, as they gradually handed over all of the land, they set up a national organisation called Fundación Rewilding Chile. It is these fine folks who now do the work in-country and who I got in touch with towards the end of last year when I realised that I could escape the British winter for three weeks in January and head off to Patagonia.

Quick back-story, I used to work in Chile, so any excuse to go back and see old friends and you won’t see me for dust, and this excuse involved introducing my gap year-bound son to a country I love. It was also a great opportunity to see how they do rewilding on the other side of the world, and it was an eye-opener.

Let’s start with a bit of hugely generalised context. Over the last hundred or so years, many of the accessible parts of southern Chile were given over to huge sheep or cattle ranches—estancias. As with comparable situations in the UK, this pushed out the native wildlife—herbivores such as guanaco (like alpacas) or ñandú (like ostriches). Predators, like foxes and puma (mountain lion) were persecuted, lost their prey, their access routes and their territories. Carrion birds like condors also started to fall foul of poison used to kill puma. The worst of it was that these ranches were never profitable, and were largely an imported system set up by European settlers to try to keep the wool trade alive.

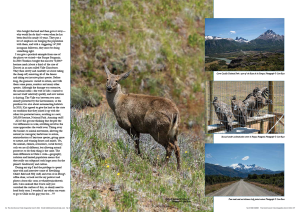

The ranches were huge and eminently unsuitable for sheep, with mountains, glaciers, huge lakes and rivers, leading into dryer, more fragile steppes that head into Argentina. The overgrazing caused a lot of damage and not only pushed out the native wildlife, but cut off vital corridors for rarer species like the Chilean national symbol—the Huemul deer—to travel through. This species is now so rare, that on one day in the field I was incredibly lucky to see six of the animals, about 0.5% of the entire wild global population.

But I digress! Rewilding Chile have a three-pronged approach to their work:

By working with Tomkins Conservation, they raise money to buy land from farmers that is strategically important for biodiversity, rewild it, and then when the bureaucracy is sorted out (which can take years) gift it to the State on the condition that it is given National Park status—so is fully protected. National Parks in Chile follow the American ‘protectionist’ model as opposed to the British ‘do what you like’ model, which is appropriate when you have as much space as they do;

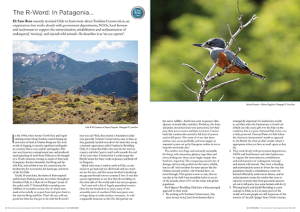

They work closely with government departments, NGOs and local farmers and other landowners to support the reintroduction, rehabilitation and acclimatisation of endangered, ‘missing’, and injured wild animals. They have a breeding and reintroduction centre to boost the very low population ñandú, a rehabilitation centre for huemul affected by cattle-borne disease, and an acclimatisation centre for condor that were in captivity or nearly died from poisoned carcasses set out to kill puma (yes, some farmers still do it);

Winning hearts and minds! Rewilding is a new concept in Chile, as it is in many parts of the world, and some people are still suspicious of the motives of the rich ‘gringo’ from North America who bought the land and then gave it away—why would he do that?—even when he has been dead for nearly 10 years. They put a lot of emphasis on bringing the population with them, and with a staggering 147,000 instagram followers, they must be doing something right.

I can give a practical example from one of the places we visited—the Parque Patagonia. In 2004 Tomkins bought the massive 70,000+ hectare ranch (about a third of the size of Dorset) in an area called Valle Chacabuco. They then slowly and carefully set about taking the sheep off, removing all of the fences and taking out invasive plant species. Before long, the guanacos started to return, and with them some puma, condors and many other species. Although the damage was extensive, the natural order—the web of life—started to reassert itself relatively quickly, and now nature is thriving. The Valle was between two areas already protected by the Government, so the purchase was also about reconnecting habitats. In 2018, Kris agreed to give the land to the state on condition that they joined it up with the other two protected areas, resulting in a new, 260,000 hectare, National Park. Amazing stuff!

All of this got me thinking that despite the vast differences in scale, rewilding involves the same approaches the world over. Taking away the barriers to animal movement, allowing the natural (or surrogate) herbivores to return, reintroduction of keystone species, giving space to nature, and winning hearts and minds. Yes, the animals, climate, economics, social history, soils etc are all different, but allowing natural processes to do their thing is the same. The main difference in Chile is scale—geography, isolation and limited population means that they really can safeguard such huge areas for the planet’s biodiversity and carbon.

During my trip I had the privilege to spend time with and interview some of Rewilding Chile’s field and HQ staff, and even sit in Doug’s office chair, so look out for my podcast and photos about this soon at whatifyoujustleaveit.info. I also realised that I have only just scratched the surface of this, so clearly need to head back soon. I wonder if my other son wants to go to Chile on his gap year too…???