I had a close encounter with three robins over the holiday. Not in the garden or the countryside—these were sitting on our mantelpiece, as images on Christmas cards. And it set me thinking—why do we associate robins with Christmas, or indeed with winter, when there are two other, related birds, which would be much more appropriate?

I suppose it’s to do with familiarity, really. The robin is officially our best-loved bird—it has been Britain’s national one since 1960, and we are drawn irresistibly to it by the charm—its rounded shape and big dark eyes, its wistful song which, in contrast to other birdsong, continues through the winter, and that flaming scarlet breast. Plus of course the tameness—robins fly into houses, follow you in the garden, nest in your watering can, perch on your spade. They inspire warm feelings, and Christmas is the warm-feelings time par excellence,

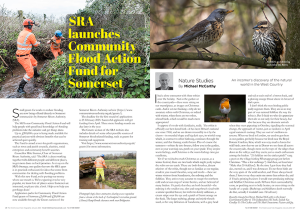

Yet if we wished to mark Christmas as a season, as a winter festival, there are two birds which might justly replace the robin on our cards. These are both thrushes, distant relatives of the robin, though not as familiar as our regular, resident year-round thrushes, song and mistle—these are winter visitors from Scandinavia, the redwing and the fieldfare. They arrive every autumn to escape the northern cold and eat our crop of winter berries, and are beloved of many birders. It’s partly that they are both beautiful—the redwing is the smaller one, slim and song thrush-sized with a similar speckled breast, but with two lovely additions, a cream stripe over the eye and a patch of burnt orange on the flank. The larger redwing, plump and mistle thrush-sized, is the very definition of handsome, with a grey head and tail at each end of a brown back, and a glowing orange throat above its breast of dark spots.

I don’t think the non-birding public really registers them. They are in no way part of our national folklore the way the robin is. But I think we who do appreciate them do so not only for their beauty, but also because they are dramatic arrivals when they start appearing in October, signalling the seasonal change, the approach of winter, just as swallows in April signal summer’s coming. They are sort of swallows-in-reverse. When we lived in London, we used to get them in our garden, probably because we lived near the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, which was very much a haven for wild birds; now that we are in Dorset we see them all across the countryside, though more on the tops of the ridges than down in the valleys; and they excite just as much enthusiasm among the birders. “21 fieldfare on the cricket pitch!” sang a post on the village birding Whatsapp group just before Christmas. “Plus a few redwings.”) And then, an hour later: “Make that 35 fieldfare!). By the time I got there they had alas, moved on, and I was downcast. To me these birds are the very spirit of the cold weather, and I have always loved them; I have to say they excite me more than robins do, and if I had a printing business I would start producing redwing and fieldfare Christmas cards. I’d have them surrounded by snow, or perching next to holly berries, or even sitting on the handle of a spade. (Redwings and fieldfares don’t normally do that, actually. I wouldn’t care. I’d sell out.)