Looking back at historical moments that happened in September, John Davis highlights women winning the right to vote

Following the recent General Election two hundred and sixty-three female Members of Parliament won seats in the House of Commons-forty per cent of the total number of members who are eligible to sit in the chamber.

This is the highest amount ever elected to represent constituents in the United Kingdom’s senior legislative body but the journey to this point has not been without its struggles and has taken over one hundred years to achieve.

Britain, compared with some other regions of the world, was slow to grant women the vote and, even then, it took years of militant persistence and sacrifice and a major world conflict to overturn the status quo.

To find the trailblazers in female emancipation you have to journey to the other side of the world, to the islands of New Zealand in fact, where laws were passed giving women the right to vote in elections as early as this month, September, in 1893.

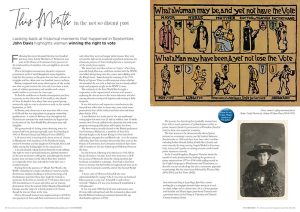

In Britain, only about one in ten men were able to vote in 1832 and this was dependent on property ownership qualifications. A series of Reform Acts throughout the Victorian era extended the male franchise by degrees but by the start of the First World War all women were still ineligible.

The groundswell of feeling about obtaining votes for women had been growing especially since the founding in 1903 of Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

It all started with a meeting in the front room of a house in Manchester with members of the Pankhurst family, mother Emmeline and her daughters Christabel, Sylvia and Adela among the leading lights in the organisation.

A local journalist, taking his lead from the word suffrage (the right to vote in political elections), dubbed members of the new movement suffragettes and although the body’s leaders were not keen on the title at first, they warmed to it especially when they realised the word ‘get’ was a component part.

Starting from the premise of ‘Deeds Not Words’, the WSPU embarked on a hectic schedule of marches, leaflet distribution, displays, heckling at political meetings, civil disobedience and what these days might be termed as terrorism. In the first six months of 1913 alone, there were 250 recorded cases of arson and other acts of wanton destruction. Even the current Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, was the target of a bomb attack on his house though he was not there at the time.

Over a thousand women were imprisoned up to 1912 for non-payment of fines and their involvement in civil unrest and, when they went on hunger strike because they were refused the right to be considered as political prisoners, the inhumane process of force feeding became a routine part of the cruel prison regime.

The movement was also to have its ‘martyr’ when forty-year-old Emily Davison, a full-time worker with the WSPU, was killed after getting onto the course and colliding with the King’s horse Anmer during the running of the 1913 Derby at Epsom. There is still conjecture about whether she intended the act to be a fatal one but it certainly added tragic and poignant weight to the WSPU’s cause.

The outbreak of the First World War brought a suspension in the organisation’s activities with women replacing the absent men in the home industries and also serving abroad assisting with logistics and nursing in field hospitals.

It was this tireless and impressive contribution to the national war effort that, in many ways, now acted more persuasively than all the militant activities that had taken place before 1914.

A new Reform Act at the end of the war reaffirmed voting rights for men over 21 and ex-soldiers over 19 while women over 30 were added to the electorate but with some property-owning qualifications still in place for them.

The first woman actually elected to the British parliament was Constance Markievicz, a member of Sinn Fein. She had fought in the Easter Rising in 1916 when Irish Republicans attempted to end British rule. As is the custom still today, Sinn Fein members do not take their seats in the House of Commons, but Constance would not have been able to anyway as she was locked up in Holloway Prison at the time.

So, the honour, following a by-election in 1919, fell to Nancy (Countess or Lady) Astor who took over as M.P. for an area of Plymouth when the sitting member, her husband, succeeded to a peerage. Astor had in fact been born in America but had settled in England and went on to serve in the Commons until the end of the Second World War.

A fierce critic of Winston Churchill she once admonished him by saying: “Oh, if you were my husband I’d put poison in your tea”. Churchill is said to have retorted: “Madam, if I was your husband I would drink it with pleasure.”

It was not until 1928 that both men and women over 21 were fully enfranchised and this remained in place until Harold Wilson’s Labour government lowered the age threshold to eighteen in 1969.

The journey has been long but gradually women have been able to reach positions of political power either as prime minister (head of government) or President (head of state) in their own respective countries.

The first women to be democratically elected prime minister in a sovereign country was Sri Lanka’s Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1960 and there have been other notables including Indira Ghandi (India), Golda Meir (Israel) and more recently the long serving Angela Merkel in Germany. Italy, Latvia and Uganda are among countries with female prime ministers currently.

In the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher broke the mould of male domination by holding the position of prime minister from 1979 to 1990 while adding words to the English language in Thatcherism and Thatcherite, to describe not just an ideology but also a systematic approach to governing. She has since been followed by Theresa May (2016-2019) and Liz Truss (2022).