Looking back at historical moments that happened in April, John Davis highlights the search for the North West Passage.

Since the time when sailors first put to sea on ocean going voyages the Holy Grail of seafaring was finding the North West Passage.

The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans could traditionally be linked by rounding the tempestuous Cape Horn at the tip of South America and, from the beginning of the twentieth century, through the Panama Canal, but could the two great waterways of the world be united with a sea route traversing the Arctic regions of the north?

Even as far back as the Vikings, there was some exploration of Arctic waters as these intrepid Norse mariners island hopped from Iceland to Greenland and even, so archaeologists now believe, the eastern coast of Canada and America.

Later some of the notable explorers of the fifteenth century including Columbus, Da Gama and Diaz flirted with the notion of finding a North West Passage while they were to be followed in the centuries that came after by sailors like Martin Frobisher, Henry Hudson, William Baffin and James Cook.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the search became the obsession of Sir John Barrow, second secretary of the Admiralty between 1804 and 1845. He encouraged leading adventurers of the time like John Ross and William Edward Parry to push the boundaries around Canada’s Arctic waterways.

Then, at the beginning of 1845, Barrow agitated for a full-scale expedition to the frozen north to locate this elusive seaway once and for all time. A number of candidates were touted to lead the two-ship expedition but some claimed to be retired and others flatly refused. Finally, the task was handed to Sir John Franklin (59) who had already made several trips to the region. Franklin was to be in overall charge with James Fitzjames as captain of The Erebus and the second ship, The Terror, under the command of Francis Crozier. Few of the crew had experience of sailing in such frozen and deserted climes.

Both vessels had been fitted with steam engines and screw propellers and had interior heating systems. To improve their seaworthiness, the ships had heavier wooden beams and iron plates built into their bows and both the rudder and the propellers could be retracted to protect them from ice. Victuallers supplied the ships with enough food to last for three years.

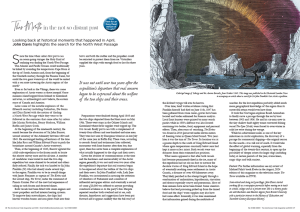

Preparations were finalised during April 1845 and the two ships departed from the Kent coast on May 19th. There were stops in the Orkney Islands and Greenland where fresh supplies were topped up. The two vessels finally put to sea with a complement of twenty-four officers and one-hundred-and-nine men. They were last seen by European witnesses in late July of the same year in Baffin Bay. There were, according to records found and testimonies later collected, encounters with Inuit hunters after then but, that apart, there has never been a complete explanation of what actually happened to the ships and their crews.

Given the absence of communications at the time and the harshness and inaccessibility of the Arctic region generally, it was not until over two years after the expedition’s departure that real concern began to be expressed about the welfare of the two ships and their crews. Sir John Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin, was instrumental in arousing the attention of Members of Parliament and a number of influential newspaper editors and eventually a reward of some £20,000 was offered to anyone providing conclusive evidence as to the party’s fate. Despite repeated searches both overland and at sea, only theories, hypotheses and suggestions have been put forward and it appears unlikely that the full story of the ill-fated voyage will ever be known.

Over time, brief written evidence stating that Franklin himself had died on June 11th, 1847 has been gathered from stone cairns, graves have been located and bodies exhumed for forensic analysis. Local Inuit hunters were quizzed by many search parties while in 1959 a lifeboat was also located containing two bodies, food, equipment and personal effects. Then, after years of searching, The Erebus was found in 2014 preserved under eleven metres of freezing water in Queen Maud Sound. Two years later it was the turn of The Terror. Its location was at a greater depth to the south of King Edward Island where again temperatures constantly below zero had kept it more or less intact. Both vessels were vast distances from their estimated last positions.

What seems apparent is that after both vessels had become permanently fixed in the ice, many of the expedition had set out on foot to traverse the desolate wastes of King Edward Island in the hope of eventually reaching some settlements in Arctic Canada, a distance of over 400 kilometres away. They likely perished in the attempt largely through a combination of malnutrition, hypothermia, starvation and disease especially scurvy and pneumonia. Most of their remains have never been found. Some scientists believe that lead poisoning picked up from the tinned food and the ships’ water supplies may also have had some effect. Ironically, it was later maintained that information gained during the multitude of searches for the lost expedition probably added much more geographical knowledge of the region than its successful return would ever have done.

It took the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen to finally carve a passage through the ice by boat between 1903 and 1906. He and his six-man crew in the tiny shallow draft eighty tonne converted fishing vessel The Gjoa (Yoah) were forced to over-winter in solid ice twice during the voyage.

While his achievement ranks as one of the key milestones in Arctic exploration, the discovery of a passage for commercial shipping—the original reason for the search—was still out of reach. It would take the effect of global warming, especially from the beginning of the twenty-first century, to open up the possibility of deeper routes for larger ships including today, at certain periods of the year, cruise liners, cargo ships and bulk carriers.

Footnote: For further information see my review of Michael Palin’s book Erebus in the August, 2024 edition of this magazine or the television series The Terror available on ITVX.