At about 3.00 p.m. on Friday, December 14th, 1911, Norway’s Roald Amundsen and his party of intrepid explorers reached the point in Antarctica they believed to be the exact geographical location of the South Pole.

There were five men in the party. In addition to Amundsen, they were Loav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting. They celebrated with a simple meal of seal meat.

For several days they checked their location (90 degrees South) from the position of the Sun in the sky. They took readings from numerous points around the Pole to make sure they were in the exact place.

Once certain of their bearings, they erected a small tent proudly flying the Norwegian flag from the pole. Inside they left a message for their great rival, Britain’s Captain Robert Falcon Scott, who they assumed was not far behind, as well as a letter to the ruler of Norway, King Haakon.

It had taken Amundsen and his party about fifty-seven days to complete the 1300km (800 mile) trek relying on supply depots of stores they had set up previously on the outward trek. The group had gambled by using a new and unexplored route.

The return journey to base camp, on the Ross Ice Shelf, was done in a shorter time with some of the remaining dogs but then followed a frustrating month-long voyage in their ship Fram to the island of Tasmania where finally on March 7th the historic news was announced to the world.

Meanwhile Scott and his final chosen party of Laurence Oates, Edgar Evans, Henry Bowers and Edward Wilson faced a journey that was about 90km (55 miles) longer than that of Amundsen. They started their journey ten days later from Ross Island and were following a course first explored by another famous polar explorer Ernest Shackleton in 1909.

Scott finally reached the South Pole on January 17th, 1912. There was understandably huge disappointment when they found Amundsen’s tent and the Norwegian flag. They staged their own flag raising and photographic ceremony and then, after several days rest, set out on the return journey.

The party hit atrocious weather on the way back with all members suffering from exhaustion, malnutrition and hypothermia as well as being generally low in spirits. Evans died soon after leaving the South Pole and Oates died later after walking outside the tent because he did not want his condition to slow up the others. Finally, sometime towards the end of March, Scott, Bowers and Wilson died together in their shelter during bad storms. They were just 11 miles (18km) from the next supply depot.

A search party was sent out to look for them at the end of the Antarctic winter in 1912 and they were eventually found inside their sleeping bags in a snow-covered tent on November 12th. The last words written in Scott’s diary poignantly pleaded, “For God’s sake look after our people.”

Near the spot where the bodies were found a simple cairn of snow and ice was erected with a cross on the top. It must qualify as the loneliest and bleakest graveyard in the world. A second memorial to Scott and his party was also erected on Observation Hill near McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. It bears the last line of Lord Tennyson’s poem Ulysses: “To strive, to seek to find and not to yield.”

Following news of the deaths of the British party, members of the public rallied immediately to establish funds to support their families. Since 1912, a large number of memorials and statues have been erected to Scott in different parts of the country.

In essence then, with the different routes used and the time variation taken into consideration, why did one party successfully reach the South Pole and return safely while the other paid the ultimate sacrifice.

For the journey to the Pole, Scott wanted to use motorised sledges and horses but, in the end, these proved to be unsatisfactory and the men pulled the sledges themselves using straps around their shoulders and upper bodies. They did not use skis and the team largely wore layered outfits made from wool. In addition, their daily food intake was not sufficient to compensate for the energy they were expending and as a result they first lost body fat and then muscle. A shortage of fuel through leakage often meant that food was eaten cold while a lack of Vitamin C resulted in them contracting scurvy, another debilitating factor.

Amundsen’s team used dog teams throughout-some fifty animals in all were taken. All of the men, with their Nordic background, were expert skiers and dog handlers and this helped them move much more quickly. Amundsen, for whom the weather conditions were much kinder, also favoured outfits of sealskin and fur, something he had learned while living with the Inuit people of the Arctic. The Inuit had also shown him that meat, often eaten raw, would help prevent scurvy so, as dogs began to drop out, they were used to feed the stronger animals and the men themselves.

After the event, Amundsen agonised about the death of Scott and his group. On his approach to polar exploration generally Amundsen once noted: “Victory awaits him who has everything in order; luck people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.”

Footnote:

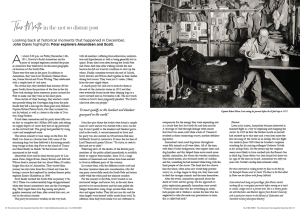

Later in his career, Amundsen became interested in manned flight as a way of exploring and mapping the Arctic. In 1925 he flew the furthest north an aircraft had reached up to that time and a year later made the first crossing of the Arctic in an airship. His last flight was made in June 1928 when he boarded a seaplane searching for his missing colleague Umberto Nobile in his airship Italia. On the return trip the seaplane seems most likely to have crashed into the Barents Sea in thick fog. Some debris was later found but there was no sign of the men on board. Amundsen was fifty-six years old. Nobile’s airship later returned safely.

For those interested in reading further try Race to the Pole by Sir Ranulph Fiennes and/or South: The Race to the Pole edited by Pieter van der Merwe with Jeremy Mitchell.