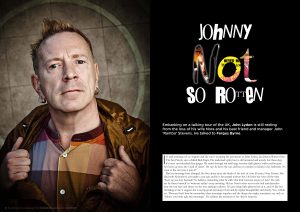

Embarking on a talking tour of the UK, John Lydon is still reeling from the loss of his wife Nora and his best friend and manager John ‘Rambo’ Stevens. He talked to Fergus Byrne.

It’s mid-morning in Los Angeles and the sun is warming the pavements as John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten from The Sex Pistols, sips a chilled Red Stripe. His trademark spiky hair is still untamed and unruly, but these days it’s more sun-bleached than ginger. He stares through red and beige tortoise-shell glasses, wide eyed because he’s been up since the ‘crack of dawn’. He says he loves the sun and has no curtains or blinds in his bedroom. ‘As soon as the sun rises, I join it!’

But his mornings have changed. He lives alone since the death of his wife of over 40 years, Nora Forster. She died with Alzheimer’s just under a year ago and he is devastated without her. He hears her voice all the time. “Gets up you lazy bastards” he bellows, mimicking what he calls ‘that little German accent of hers’. He tells me he forces himself to ‘welcome reality’ every morning. He has Nora’s ashes next to the bed and describes how the sun rises and shines on her urn, making it glisten. ‘It’s got cheap little glisteny bits in it, and it’s like her twinkling at me.’ I suggest she is saying good morning to him and he replies thoughtfully and slowly, ‘Yes, I think so…’ Because that’s how he remembers their mornings together and the things she might sometimes say, such as: “John’s, you looks ugly this mornings”. He relishes the memory of her ‘dryest humour.’

Nora is not the only loss in his life at the moment. His best friend and manager John “Rambo” Stevens died suddenly after complications from an aortic heart dissection in December. However, despite explaining how ‘very hard and seriously puzzling’ it is for him to deal with the grief—‘in the same year to lose your best friend and the love of your life, your wife’—John points out there are worse things going on around the world and tries to use that thought to fend off the pain. But like anyone else who has tried that tack, he likely knows it’s a very thin defence against the pain of loss.

In May he is coming to England to start a spoken word tour. Entitled, I Could Be Wrong, I Could Be Right 2024, it is being billed as Untamed, Unscripted and Uncensored. The shows may well be a revelation for those that only know of Johnny Rotten, the “hell-raising” lead singer of the Sex Pistols. He was never really what you could call a “hell-raiser”. However, he did swear on national television once, and let’s face it, that’s often enough for headline hungry tabloids to build a profile on.

Although the Sex Pistols were only together for a little over two years and despite it now being more than 45 year since the band broke up, for many people his legacy is still stuck in the late seventies world of punk. But in fact he was quickly disillusioned by the media hype that had been cleverly manipulated by the band’s manager, Malcolm McLaren. He knows he was a mouthy, angry young man then, but the exploitation and the image management has stuck, even though he has since founded and been the lead singer with Public Image Limited (PiL), a band that has produced eleven studio albums and been widely regarded as one of the most innovative and influential bands of their era.

He is well aware that none of that will change the general perception of who he is. ‘There’s so many people out there that deliberately want to get me wrong ’he says. ‘And I’m frightened, sort of, that they’ll misuse whatever information I’ve provided.’ He admits he ‘might not have got all of it right, but I think I’m on a good and healthy road. They got it wrong about me right at the start. And they’re continuing that line of torture. It’s harmful, and it’s hurtful to misjudge a person. And the trouble with being in the public eye is you’re constantly misjudged.’

And that begs the question of whether he thinks what he has to say, musically or in spoken word is relevant today. ‘I’ve no idea’ he says. ‘I just deal with the situations at hand that I have to cope with. And thereby try to explain them, not only to myself, but to others. If they’re of some use to outside folk, then that’s all well and good. But internally, I’m in a constant state of self correction and self doubt, and phobias, and problems, and learning to deal with them—honestly and deeply considering all the aspects and points of view therein. That’s an ongoing process. I’m very far from becoming a perfect human being.’

The reality of this tour, whether in part to change misjudgement and perception or to determine whether he has a future in music, is it’s a way for one man to get back up off the floor after being knocked sideways by grief. He’s doing the gigs as much for Nora and Rambo as he is for himself, and for a fan base that he says ‘really wouldn’t want me to fall back into and wallow in self pity.’ He says Nora is in his head, ‘telling me get out and confront the situation, deal with it.’ There is no script he says, ‘no flashing Tiller Girls to come on and disco lights, no fully fledged comedian with predetermined jokes. No! it’s Johnny. I sink or swim by the moment.’

And he’s not one that might be short of a story or two. Born left handed he remembers how the nuns would hit him with the side of a ruler to try to get him to use his right hand. He laughs at the memory, “Oh he’s a devil that one!” he says, this time mimicking an Irish accent.

As a young boy he got meningitis and spent a year away from school, some of the time in a coma. ‘I came back with glasses’ he remembers. ‘Nobody knew me. I didn’t know anyone. My memory wasn’t quite back together again because of the coma.’ He says they spent the next year or two trying to convince him that he was really right-handed. ‘That was wicked beyond belief. Because that was the only thing that my brain remembered—that I was instinctively left!’

He developed a natural tendency to disagree with authority, especially when it appeared to be unjust. And although catching up after time spent out of education, he was no fool and often quick to answer back when treated disrespectfully. Now he is 68 years old and I ask him what has changed? ‘I would hope an enormous amount’ he says ‘like a fine wine you must mature with age.’ But he doesn’t think he has calmed down that much. ‘I still instinctively will stand up for the disenfranchised and always be an angry young man.’ He smiles, ‘Growing old distastefully.’

The last few years of his life with Nora were pretty grown up. He was her full-time carer as she gradually lost her memory. At one point he remembers how she suddenly stopped in the ‘fast lane’ of a six lane highway in Los Angeles. A former racing driver from her youth in Germany she had forgotten where she was. ‘And that’s when I knew this was bad’ he recalls. He doesn’t drive but managed to somehow manoeuvre the car back to their home.

They got an Alzheimer’s diagnosis and she began to slowly develop different phases ‘in and out of conscious behaviour.’ There was a period when he would have to keep all the doors locked. ‘Because if she got out she would run for miles and get lost, and do that at high speed too. She could run like a gazelle. And so I’d have to get police hunts out for her.’ She would manage to go for miles trying to find somewhere familiar. Coming back in the back of a police car he remembers how she found it very amusing and would jump out with a cheery ‘“Hello Johnny!”—like she’d a great time.’

He tells me that, strangely, his upbringing prepared him for the role of carer. His mother was ‘ill a lot’ and had miscarriages when he was young. And his Dad worked away, leaving John to look after his younger siblings and deal with his mother’s illness. ‘So I was fully prepared to deal with Nora when it became very, very compromising for her.’ Especially as he had strong memories of the period after he had meningitis and his own memory became an issue for nearly four years. ‘I learned a huge lesson in life from that very experience. I could understand and empathise with her greatly.’

They never had children. ‘We nearly did’ he tells me. ‘But she panicked and had an abortion.’ He was on tour at the time and says she was worried that it would be a pressure on him. ‘It broke both of our hearts at the time, but in a very odd way, it brought us closer together.’

Whatever comes of the, I Could Be Wrong, I Could Be Right 2024, tour, John Lydon hasn’t mellowed with age and says ‘I’ll deal with what I’m asked. Because I don’t want to disappoint people by being dishonest.’

He says he has no fear of honesty but rather a fear of not being honest. ‘I don’t want to start waxing lyrical and being fabulous. Because the temptation when you’re on a stage is to do exactly everything that is wrong in life.’ And that’s a temptation that he has eschewed for a very long time.

John Lydon ‘I Could Be Wrong, I Could Be Right 2024’, starts in Brighton on May 1st. He will be at the Guildhall in Axminster on May 15th. Tickets are available from: https://www.axminster-guildhall.co.uk/whats-on/john-lydon