Flying arms into America is not a recommended activity, but when Fergus Byrne took a personal journey involving a Heavyweight Boxing Champion, a little grave robbing and a possible knighthood, arming a small New York Arts Centre made sense.

A nearly 8,000 mile round-trip to attend a private view in a small Arts Centre in New York may seem excessive to some, but to me, travelling to New York to view the mummified arm of a 19th century pugilist was more than just following a wacky story.

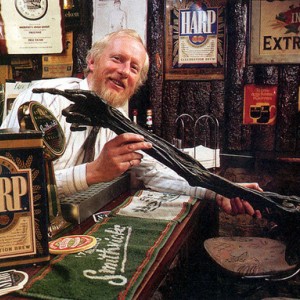

The right arm of ‘Sir’ Dan Donnelly, a famous Irish bare-fisted boxer, who died in 1820, has been a feature in my family since it arrived at our home in 1953 – in fact it has featured in the family even longer than I have!

A gruesome sport to many, the art of boxing is something that has gripped the imagination of young boys for centuries. ‘Heavyweight champion of the world’ we would cry – little boys imitating the antics of Muhammad Ali. More than a hundred years before Ali, young lads had cheered heroes like Tom Cribb, George Cooper and Tom Hall, who fought vicious battles before the Marquis of Queensbery rules took the knuckle out of the sport. Prior to that, as young Dan Donnelly was avoiding school, hard men fought under the Broughton rules, which did not forbid head butting, eye gouging, hair pulling or wrestling. In fact it was Jack Broughton who invented the boxing glove, though it was only for use in sparring and exhibitions. For the real thing, the gloves came off.

Like many stories from the era, the tale of Dan Donnelly has likely been slightly embellished in the telling over the years, and is perhaps all the better for that. Born the ninth child of a family of seventeen, including four sets of twins, Dan was by all accounts a sturdy child who survived in a time when many didn’t. Little is known of his youth, although the inevitable stories of his humility, bravery and care for others, help to create the image of a lad any mother could be proud of. One story tells of how, after coming to the rescue of a young girl being attacked, he was so badly beaten that a surgeon suggested his arm would have to be amputated. Thankfully, Dr Abraham Colles, later to give his name to the Colles Fracture, was to save Donnelly’s arm and make this story possible.

Several versions of how Donnelly’s prowess in the ring was discovered have been written down over the years, but the favoured account is that he came to the aid of his elderly father who was being bullied by a giant sailor in a bar. Apparently word spread of his bravery and a local champion, jealous of his reputation, threw down a challenge, which Donnelly reluctantly accepted. He dispensed with the challenger in the 16th round and found himself the subject of much admiration. He was taken on by a trainer and manager, one of whom was Robert Barclay Allardice, a personal friend of William Pitt ‘the Younger’ and Earl of Monteith and Airth. Donnelly was taught the rudiments of bare-fisted fighting and groomed for a bout with prominent English pugilist Tom Hall. On September 14th, 1814, an estimated twenty-thousand people gathered in a natural amphitheatre in the Curragh in County Kildare, Ireland, to watch the bout. Donnelly defeated Hall and the location was later named ‘Donnelly’s Hollow’.

Fifteen months later, Donnelly was to fight the Staffordshire ‘Bargeman’, George Cooper, at the same spot. Known as a courageous, ‘first-rate ringman’, Cooper gave Donnelly and his fans plenty of cause for concern, as a hard fought battle lasted until the 11th round when Donnelly felled Cooper and broke his jaw. As Donnelly left the ring and strode up to the edge of the Hollow there were scenes of incredible jubilation. Borne on the shoulders of his fans, as his mother led a procession of cheering crowds back to his home that evening, it is said that she frequently slapped her naked bosom exclaiming “That’s the breast that suckled him; that’s the breast that suckled him!” What greater pride could a mother show?! To this day the holes dug to mark his footsteps where he strode to the top of ‘Donnelly’s Hollow’ are gleefully walked in by picnicking families on the Curragh plains.

Like many that have tasted fame, Donnelly fell victim to what is known as, the ‘demon drink’. His attempts to retire and run a pub led to increasing debts, and he left his family to raise money through exhibition bouts. He had one more ‘famous’ battle to complete, however, before finally retiring. On July 21st, 1819, Donnelly battled with ‘The Battersea Gardener’, Tom Oliver, at Crawley Downs in Sussex. Eventually winning with a dramatic right hand in the 34th round, legend has it that he was subsequently knighted by the Prince Regent (later King George IV).

‘Sir’ Dan Donnelly died the following year at the age of 32. Obituaries and comment flowed poetically throughout Britain, and, though he died penniless, funds were raised from public donations to create a memorial to him. Ironically his corpse was worth more then he was. Six days after his death, his grave was robbed and the body sold to a surgeon. Following a public outcry the surgeon returned the body – minus the famous right arm. It was coated with preservative and used by students in Edinburgh University for many years, before touring Britain in a travelling circus. In 1953 it was presented to my father and took pride of place in the family pub. Throughout my life thousands of people came to see it, and when my late brother Des sold the business ten years ago, he hoped to take the arm on tour again one day. Sadly, he died before that wish came true, and last month the arm was brought to America to be exhibited in, ‘A Celebration of the Celtic Warrior’.

Eleven members of my family made the journey to New York to represent my brother, and ‘Sir’ Dan, and of the many tributes I read, one seemed most poignant. It was spoken, with tears in his eyes, by Donnelly’s close friend Richard Dowden on March 22nd, 1820: “He, who but a few short days ago was the glory of our land; he, whose intellectual and corporal energies were the theme of every tongue; he, who basked in all the sunshine of prosperity; he, who in all the pride of conscious dignity stood on the loftiest pinnacle of fame and honour; he, whose virtues were as the refreshing dews of Heaven; he – is gone!”

But the arm lives on…