The feeling of being in on a secret is a curiously enjoyable one, even if it’s not a deliberately-kept secret, just something that most people don’t know about. I have that feeling with winter aconites. Because I’ve come to realise that most people are not aware of their existence, even though these flowers form one of the highlights of nature at the start of the year. Certainly, looking back at the winter which has just ended, and which I remember as wet and dark and muddy, they were a highlight indeed.

There are few plants which actually have their main flowering season in January. Winter heliotrope is one, with its big green leaves and pale mauve flowers with their marzipan scent, and hazel is another—it’s in January that hazel produces those dangling yellow catkins. But winter aconites are the best. They’re in the buttercup family, though a lot less common than our various buttercup species, and they’re particularly pretty: before the petals fully open they are striking golden globes, bright yellow heads sitting on top of a neck-ruff of green leaves, as it were, so that in Suffolk, according to Richard Mabey in Flora Britannica, they are known as ‘choirboys’. And in direct sunlight they seem to glow.

I originally encountered them when we lived near Kew Gardens, and I started noticing this patch of small bright blooms outside the visitor centre which flowered before everything else. I looked them up, but I couldn’t find much written about them. They seem to be on very few people’s radar. Perhaps it’s because they’re not native plants, but introductions from continental Europe, although they’ve been here since at least the sixteenth century. They’re in gardens, and as escapes in places like parks and churchyards and roadside verges, but here’s another peculiarity about them—they’re found much more in eastern England, in East Anglia in particular, than in the west. And indeed, when I got an email on January 20 which said: “Small signs of spring here, despite the raw weather. I love the way the aconite glows like a little lamp” it was from my friend Jeremy, who lives in Suffolk.

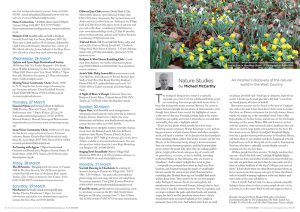

But winter aconites can be found in the west of England too, and in the time I have been here I have come to realise that there are Dorset enthusiasts for this little-known flower which, we might say, is the snowdrop’s rival. One is Mrs Sylvia Gallia of Nether Cerne, and on one of the few bright mornings of the winter Robin Mills and I went to see her with her aconites, some scattered under a mulberry tree and others in a lovely large patch in her garden by the river. We then went on to see Sylvia’s friend Jack Wingfield-Digby, who has a garden teeming with aconites in Hazelbury Bryan, and from there to see Andrew and Josie Langmead at Stock Gaylard house with its deer park on the road to Sturminister Newton, who have a splendid aconite display around a weeping ash tree on their lawn.

All these people love their aconites. “In bright sunshine they turn on—they’re like little suns,” said Jack Wingfield-Digby. “We look out from our kitchen window and when it’s dull you can only just pick them out, but when the sun comes out it’s a blaze of yellow. Suddenly it’s like there’s 100 per cent more of them.” I don’t doubt there are other Dorset aconite-lovers; in fact, it seems to me that anyone who gets to know this flower, with its beautiful warming brightness at the very darkest and barest time of the year, will fall for it.

I love it myself. And as I said, it is also a curiously enjoyable feeling to know about it when so many people do not—to be, as it were, in on the secret. But I’m only too happy to share it.

Recently relocated to Dorset, Michael McCarthy is the former Environment Editor of The Independent. His books include Say Goodbye To The Cuckoo and The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy.