Until the age of thirty, Mary Kingsley, who was born in October 1862, lived a quiet, sheltered, uneventful life even by Victorian standards.

With her father, a doctor and travel writer, away for much of the time in both Africa and North America and a fragile mother who was often ill, Mary was largely responsible for bringing up her younger brother and running the household on a tight budget. There was no time for formal schooling as such and she educated herself from the books that she found in her father’s well-stocked library.

Then in 1892 there was a massive sea-change. Both her parents died within the space of five weeks and Mary, who was the niece of the writer and social reformer Charles Kingsley, could, with the benefit of her inheritance, pursue interests she had been harbouring for some time.

Despite the fact it was unheard of during the late nineteenth century for a woman to embark on such adventurous journeys, she was determined to travel to Africa to see at first hand the places she had read about in her father’s books during those long, lonely days at home in the library. While there she also intended to carry out research so that she could finish writing a book about African law and religion her father had been unable to complete at the time of his death.

Over the next three years she not only achieved this aim but also gained enough fascinating material for several gripping books of her own as she brushed aside convention by climbing mountains, hacking her way through dense jungles, wading across swamps, encountering cannibals and canoeing down crocodile infested rivers.

During one incident in her travels along the Ogooue River, a crocodile attempted to board the canoe in which she was travelling. In her book Travels in West Africa, she described the attack. “He chose to get his front legs over the stern of the canoe and endeavour to improve our acquaintance. I had to retire to the bows to keep the balance right and fetch him a clip on the snout with the paddle when he withdrew and I paddled into the very middle of the lagoon hoping the water was too deep for him to repeat the performance”.

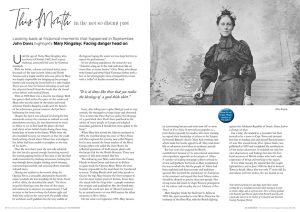

In her climbing expeditions she noted she was “forced to cling on to the rock wall more like an insect than an insect hunter.” Once Mary, who always wore formal and often black Victorian clothes with a hat, as her photographs show, emerged from a river with a ‘collar’ of leeches around her neck.

Later, after falling into a spike filled pit used to trap animals, she managed to escape injury and observed, “It is at times like these that you realise the blessings of a good thick skirt. Had I have paid heed to the advice of many people in Europe and adopted masculine garments, I should have been spiked to the bone.”

When Mary first visited the African continent in 1893, she travelled along the coast of West Africa and then explored the country now called Nigeria. In the area around the lower reaches of the River Congo (often now called the Zaire River) she collected specimens of both insects, plants and freshwater fish for the British Museum. Three new species of fish were named after her.

The following year, Mary sailed from the Canary Islands to Sierra Leone and then on to Gabon to again reach the Ogooue River. When the river became impassable to the steamboat she transferred to canoe. Trading British cloth and other goods to finance the trip, Mary became the first European to visit the more remote parts of Gabon. It was here she stayed with the Fang tribe—a people notorious for savagery and cannibalism. She also found time to climb the south east face of Mount Cameroon by an untried route—at over 4000 metres the tallest mountain in West Africa.

On her return to England in 1895, Mary became an entertaining lecturer and took time off to write Travels in West Africa. It proved very popular as a travel book especially for readers who were wanting to expand their knowledge of places in the Empire far beyond Britain’s shores. Mary had a writing style which made her books appeal to all. They read more like an adventure novel than an academic journal.

But her views also angered the British establishment because of its anti-colonial sentiments and empathetic approach to the people of Africa. A number of leading newspaper editors refused to review and publicise her book as Mary condemned the way in which she felt the people of Africa had been exploited and their customs and traditions ignored. She resented the interference of Europeans in the continent and argued that local African rulers should be allowed to govern their own people. Her strong views did much to shape Western perceptions of the culture and everyday lives of Africans at that time.

Mary Kingsley made her final visit to Africa in 1899. She again intended to visit West Africa but the outbreak of the Boer War, with the British fighting against the Afrikaner Republic of South Africa, led to a change of plan.

For a time, she worked as a journalist but then trained to be a nurse in Cape Town and devoted her time to tending sick and injured Boer prisoners of war. Her second book, West African Studies, was published in 1899 and completed the recollections of her earlier adventures. It included not only her own observations and findings but also the first-hand accounts of British traders who had a wide experience of living and working in the region.

It was while nursing the injured that she caught typhoid fever and in June 1900 she died at Simon’s Town in South Africa. She was only 37 years-old. In accordance with her wishes, she was buried at sea.