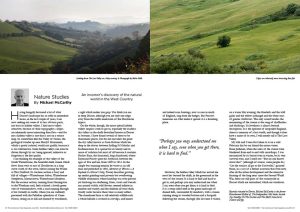

An incomer’s discovery of the natural world in the West Country

Having hungrily devoured a lot of what Dorset’s landscape has to offer in immediate terms, in the last couple of years, I am now seeking out some of its less obvious parts, not least its hidden valleys. I find most valleys attractive, because of their topography—slopes are inherently more interesting than flats—and for me a hidden valley is one that is not on a tourist map. So somewhere like the Valley of Stones, the geological wonder up near Hardy’s Monument, which is pretty isolated, would not qualify, because it is too well-known. Some hidden valleys can even be driven through by car: being ignored, unknown or forgotten is the key quality.

I am thinking for example of the valley of the South Winterborne, the beautiful chalk stream which flows from west to east of Dorchester in a long curve south of the town, before joining the Frome at West Stafford. Its western section is busy and full of villages—Winterborne Abbas, Winterborne Steepleton, Martinstown, Winterborne Monkton. But the eastern section, running from Herringston to the Wareham road, feels isolated: a lovely green vale of watermeadows, with a road running through it but virtually no traffic, where you are suddenly presented with the Palladian splendour of Came House, sitting on its hill and framed by woodlands, a sight which makes you gasp. You think you are in deep Dorset, although you are only one ridge away from the traffic maelstrom of the Dorchester bypass.

On the whole, though, the more special hidden valleys require a trek to get to, especially the roadless dry valleys in the chalk downland known in Dorset as bottoms. I have found several of these to be charismatic places, but for me one takes the prize: the dry valley known as Crete Bottom which lies deep in the downs between Sydling St Nicholas and Godmanstone. It is special for its beauty and its sense of isolation but most of all because it contains Bushes Barn, the farmstead, long abandoned, where Raymond Forcey spent his boyhood, between the ages of five and ten, from 1909 to 1914. In the simple but stunning memoir he wrote as an old man and published in 1992, Memories of Wessex—A Boyhood in a Dorset Valley, Forcey describes growing up amidst grinding rural poverty but overflowing wildlife abundance, where hardship was ever-present yet birdsong was deafening, foxes, stoats and weasels ran around visibly, wild flowers seemed infinite in number and variety, and the children all wore thick woolly socks because there were so many adders. The abandoned farm is still relatively wildlife-rich: a whole hillside is covered in cowslips, and linnets and indeed corn buntings, now so rare in much of England, sing from the hedges. But Forcey’s memories are what make it special: it is a haunting place.

However, the hidden valley which has moved me most lies beyond the chalk, in the greensand in the west of the county. It is hard to find and hard to get to, and perhaps you may understand me when I say, even when you get there, it is hard to find. It is a steep-sided cleft in the green landscape of domed hills, surrounded by meadows, with a stream running along its wooded bottom and a footpath following the stream, through (the last time I visited, on a warm May evening) the bluebells and the wild garlic and the yellow archangel and the white stars of greater stitchwort. The only sound besides the murmuring of the stream is the song of chaffinches and blackcaps. Its loveliness is almost beyond description. It is the epitome of unspoiled England, almost a memory of a lost world, and though it does have a name of its own, I will merely call it The Lost Valley.

My wife and I were first taken to it on a cold February day by our friend the nature writer Brian Jackman, when the sides of the stream were blanketed from end to end with snowdrops. I was mesmerised by its beauty even in winter, by its very survival even, and I cried out: “But no-one knows about this!” (although of course, some people do.) “Let the tourists all go to the Cotswolds,” grunted Brian, in a sort of a defiant assertion that even now, after all the urban development and the intensive farming of the long years since the Second World War, there are still parts of the countryside in Dorset which are untouched, which are wondrous.