From the moment the wheels touched the ground during the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in December 1903, it was inevitable there would be other aviation records waiting to be broken.

The Frenchman Louis Bleriot got things started with his thirty-six minutes crossing of the English Channel in July 1909 and British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown took sixteen hours to make the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean in a Vickers Vimy bi-plane in 1919.

It took another eight years until May 1927 before the American flying ace Charles Lindbergh bridged the watery divide solo when he powered his aircraft, nicknamed The Spirit of St. Louis, the 5800 kilometres between New York and Paris in thirty-three hours.

Lindbergh, who had learned his piloting skills with the military and by delivering air-mail, had journeyed considerably further than the British pair but he did benefit from an enclosed cockpit and a lighter, more reliable engine. Navigation aids were much improved and there was accurate meteorological information.

Following the flight, Lindbergh was feted wherever he went. Later he was to fly The Spirit of St. Louis to each of America’s then forty-eight states to demonstrate the reliability of flying machines and to empasise that they would become a growing force in transportation.

Despite his high-ranking celebrity status, the next phase of Lindbergh’s life was to involve tragedy and controversy. In 1932 his eldest son, also named Charles and eighteen months old, was kidnapped from the Lindbergh home one night and, after a ransom had been paid, found murdered nearby several months later. The authorities arrested a German born carpenter named Robert Hauptmann. He was tried, found guilty and executed, though family members and others still protest his innocence to this day.

The pressure on Lindbergh and his family was relentless so in 1935 he left America for Europe, not returning home until 1939. On his return he became unpopular, often being accused of pro-Nazi sympathies and arguing fervently against America’s intervention in the Second World War.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour and Germany’s declaration of war with the United States not surprisingly brought about a rapid change of opinion and throughout the conflict Lindbergh flew missions with American fighter pilots offering his expertise as a technical advisor.

In later life, Lindbergh, who died at the age of 72 in 1974, became an author, explorer and environmentalist, embracing the movement to open up national parks and protect the nation’s endangered species. He also worked to improve the welfare of indigenous peoples in the Pacific Ocean. His views were summed up in the following quotation: “All the achievements of mankind have value only to the extent that they preserve and improve the quality of life.”

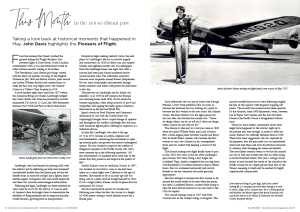

Amelia Earhart, born in Aitchison, Kansas in 1897, was hooked on air travel as soon as she had been taken on a scenic flight over California at the age of thirteen. She learned to fly at an early age and was flying solo in a plane she had bought herself by 1921. It was a bright yellow Kinner Airster bi-plane that she nicknamed The Canary.

Her first aeronautical record was broken the following year when she flew the Airster to a height of 4300 metres setting a world altitude record for a female pilot.

Soon afterwards she was put in touch with George Putnam, a New York publisher who was later to become her husband. He was looking for a pilot to become the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. He knew Earhart was the right person for the task after she told him her maxim was: “Never do things others can do or will do if there are things others cannot do and will not do.”

The chance to take part in a trial run came in 1928 when two pilots Wilmer Stultz and Louis Gordon flew a three-engine plane between Canada and Burry Port in South Wales. Amelia, who became the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air, accompanied them and was tasked with keeping a record of the flight.

The history making solo flight finally came to pass in May 1932, five years to the day after Lindbergh’s epic journey. This time, flying a new bright red Lockheed Vega, Amelia completed the crossing from Newfoundland to Northern Ireland in almost fifteen hours. She was acclaimed universally and crowds flocked to see her whenever she made personal appearances.

Her first attempt to become the first woman to fly around the world ended in disaster when her plane, this time a Lockheed Electra, crashed while trying to take off from Hawaii and had to be sent back to the USA for repairs.

The second attempt came in 1937 with Fred Noonan also in the cockpit acting as navigator. The aircraft travelled from east to west following roughly the line of the equator with frequent stopping off points. The aircraft had covered about three-quarters of the distance, some 3500 kilometres, when, between Lae in Papua New Guinea and the tiny Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean it disappeared without trace.

There has been endless speculation about what might have happened to the aviators right up to the present day, even though, in order to settle her estate, Earhart was officially declared dead in 1939. There have been suggestions she was captured by the Japanese, that the pair made it to an uninhabited island and died there and even that Earhart returned to America after changing her name and identity. The most likely scenario seems to be that the aircraft ran out of fuel and crashed into the sea while trying to locate Howland Island. This year a salvage vessel claims to have located the wreck of the aircraft in the Pacific Ocean but at a depth greater than that of the Titanic, meaning it could only be reached by highly sophisticated submersibles.