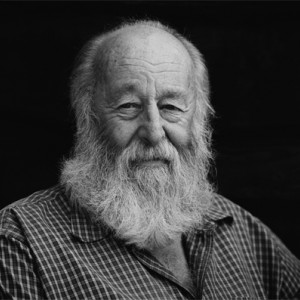

Robin Mills went to Rampisham, in West Dorset, to meet Peter Thomas, wood-turner and stick-maker. This is Peter’s story.

‘I’m a Wiltshire moonraker: born between Calne and Marlborough on the Wiltshire downs, and I grew up in a small village very much like Rampisham is today. Father was one of thirteen children: every one of his brothers and sisters farmed except him. So, sadly I was unable to inherit a farm, but there’s no doubt farming is in my genes. From a very early age I spent all my time on my uncle’s farm, and I can remember that all I ever wanted to do was farm.

I think I soon realised that peer pressure and job competition meant that I should get as good an education as possible, so I finished up going to Wye College and got a degree in agriculture. I’m not sure it did me a lot of good. I didn’t have the capital to farm on my own account, so I went into farm management. The first couple of jobs I went for, I never even mentioned the degree as it would probably have been seen as a hindrance. In those days in farming, education meant you probably weren’t much good at the practical stuff. I’ve had the beard since then: people reckoned I was too young for the job, so I grew a beard, stuck ten years on my age and got the first job I went for. That was in about 1958.

That farm was in Gloucestershire, near Stow on the Wold. We were there in 1963, all through the hard winter. We had our first child then, Wendy, and couldn’t get off the farm for eight weeks, snowed in. The dairy had just gone over from churns to bulk milk then, and obviously you couldn’t get milk out what with the 20ft snow drifts. So we got some churns dropped by helicopter, filled them from our new bulk tank and then I’d dig my way to Stow on the Wold, 5 miles away, to unload the milk, and often have to dig my way home again. That took all day, on a Fordson Major, no cab: in those days you didn’t know any different. The snow that year was still lying in the quarries up on the hills when we were haymaking in June.

I worked in Warwickshire, and in Dorset, then it was back to Gloucestershire, where we were during the two drought years of 1975 and 1976. That farm went from 400 acres when I started, to 4000 acres during the next 18 months. They had land in Scotland, in Dumfries and Galloway, and I used to drive up there once a month to look after it. If the locals chose to lay on the Scots accent a bit thick, I couldn’t make out a word of it. In’76 we finished combining in the middle of July: the crop had just died. We tried to make second cut silage, mowing grass in the morning then baling it as hay in the afternoon.

My last job came about in 1985, when I saw it advertised in the Farmer’s Weekly, managing a farm back in Dorset, and we’ve been here ever since. I’ve had to change jobs in the past quite a lot: you have to, to make any progress up the farming ladder. The main attraction to the job here was the opportunity to run our own enterprise, in this case sheep. My son Simon left college to come and run the sheep flock, and a year later my daughter Wendy and her husband joined us, so we were running it as a family business. Simon later fell in love with Australia, backpacking there in 1991, and then emigrated there with an Australian girl he’d met on our neighbour’s farm. Wendy and her husband now have a National Trust farm down in Devon. That was all about the time when things in farming were starting to get a bit sticky. We went from lambing 1200 ewes, a dairy herd, and 400 acres of arable, to just me on my own buying in ewe lambs and selling them a year later as two-tooths, with the arable land put out to contract.

By then we’d fallen in love with the area, especially Rampisham. Here, nothing changes, and that’s by virtue of the fact it’s an estate owned village. What we all value and love remains the same. So, I retired early. I was 61, the children had left, my legs weren’t too good and I needed a knee operation, and to be quite honest, I was disillusioned with farming. When I started, I never thought for one moment I’d be saying that. But everything coming from government seemed anti-rural, and to me the fun had gone out of the farming life.

I’d always liked woodwork, and if a tree blew down on the farm we always kept the trunk rather than cut it up for fire wood. I started making little coffee tables and suchlike, but it never quite filled the gap. One day I saw a second-hand lathe advertised, so I bought it without seeing it. There was no point in going to look at it: never having seen a lathe working, I wouldn’t have known what I was looking at. I got it home, set it up, and spent the next few weeks really just making a mess of pieces of wood and tools. But I became absolutely hooked. And that’s how it all started: I never had any lessons, just learned by my mistakes I suppose. I built bigger lathes: the one I’ve got now will take blanks up to about 7cwt, but I had to buy an engine hoist to lift them into place! When we moved up here, I built the shed, deliberately quite small. I thought it might stay tidier that way, but that didn’t work. At first I was just making stuff to give to friends and family, and was really amazed when I took work to village shows to find people would buy it.

At one stage we were doing about 30 shows a year. I insist on selling locally, though of course it goes all over the place afterwards. Nowadays I always do Dorset Art Weeks, and maybe 6 shows a year. I’ve got a tiny gallery here at home, and people come to me. I’ll probably spend 6 or 7 hours a day in here, turning wood, I just love it. All my wood is sourced locally, off the estate or farms nearby. There’s no need to travel far or import exotic timber, it’s all around us.

When I started doing the shows, I was shocked at people’s ignorance of the countryside. Then the Dorset Coppice Group was formed, and I joined because I thought I could help educate the public about our woodland heritage, and about the fact that of all the imported rainforest timbers, none was more attractive than our own indigenous wood.

Most of what I use would normally finish up as firewood, or rot, and we have all this wonderful resource in our woods and hedgerows not appreciated. So, as much as anything now I’m on a bit of a crusade, to try and make people aware of this. I’d never dream of cutting down a healthy living tree. Last year I was given 5 walnut trees that blew down: that’s a huge amount of timber. I’ve been at shows where people looking at my work don’t even know it’s made of wood: or, that the oak, beech or whatever species it’s made of, comes from here. I find that quite sad: also that nowadays it’s so rare for people to make things with their hands. When they do, and I teach people occasionally, they love it, and it can be very therapeutic. All this mass-produced stuff, there’s no life or soul to it: if what I do helps spread the word about the countryside a bit, I’m happy.’